Council Housing in the North East

Last year marked 100 years since the passing of the Housing and Town Planning Act, known as the Addison Act. This was an ambitious programme of government subsidies to finance the building of 500,000 houses within three years. Conceived as a way of providing "Homes fit for heroes" in the aftermath of the First World War, the programme was badly affected by the economic problems of the 1920s, and ultimately only 213,000 homes were built. However, subsequent Housing Acts in 1924 and 1930 encouraged further housing schemes by local authorities, and ultimately the inter-war Housing Acts led to the construction of 1.1 million homes.

We decided to look into the impact of the Addison Act in the North East, where housing schemes also offered a way to mitigate post-war unemployment. Schemes were adopted in towns across the area - from Banff to Stonehaven, Turriff to Rosehearty, Huntly to Gourdon - but we will focus on the schemes adopted in Aberdeen, Fraserburgh, Inverurie and Kincardineshire.

Aberdeen’s first municipal housing predated the Addison Act – tenements in Urquhart Road and Park Road were constructed in 1897. After the First World War, the long-standing problems of overcrowding and slum properties combined with a rise in expectations about the standards expected in housing provision, and the Town Council used land purchased in Torry, Hazlehead and Hilton to build social housing in the 1920s.

The Torry scheme gained government funding in 1919 under the Addison Act. The scheme proposed 600 houses: following the national pattern, ultimately only 242 were built. Designed as 3 room cottages with bathrooms and WCs, the houses had rents fixed at between £22 and £32 10s per annum – rates beyond the reach of most working men. Given the total lack of housing identified by the Medical Officer of Health in 1922, the hope was probably that this would free up cheaper, lower quality accommodation for the poorer classes.

The architect, D & J.R. McMillan, designed a series of smaller roads coming off the external roads, with a bowling green and tennis court in the centre. Every house would have a scullery and bathroom. The proposed names of the roads: Queen Mary Gardens, King Gardens, Haig Gardens, Allenby Gardens and Beatty Gardens, mixed the patriotic with a recognition of the recent conflict, with the latter three named for First World War military leaders.

Unfortunately, the Town Council struggled to obtain the necessary funding for the scheme. The costs spiralled to such an extent that the ratepayers ended up contributing more than the Government and eventually only the first installment of the scheme, 20 houses, went ahead on schedule (the site was further developed later in the 1920s). This is likely to have been houses to the north of the site, around Gallowhill Road.

There were complaints in the Fraserburgh Herald about the cost of the houses (£1200 per house) and the high rentals, which were too high for ordinary workers. It was also suggested that there was no need for additional housing, although the high number of applications (70) for the 20 houses would seem to suggest otherwise.

This complaint would seem to be born out by the list of preferred tenants agreed by the Town Council in November 1921. In line with the "Homes fit for Heroes", preference was explicitly given to ex-servicemen and the widows of men who were killed on active service: one of the larger 6 room properties was given to the widow of Lieutenant George Bradbury. A list of the 20 successful applications from the Town Council meeting in November 1921 supports the idea that these were not for the poorest workers: successful applicants were largely tradesmen, merchants and skippers, but a Dock Superintendent, teacher and MA were also listed.

Inverurie

Kincardineshire

The Housing Act also had an impact in rural areas of Kincardine, Banff and Aberdeen counties. The Kincardine County Sanitary Inspector reported on the poor quality of rural housing for the working classes in 1919, which in turn was leading to health problems including high infant mortality. The following example from the 1919 St Cyrus District Sanitary Inspector report will give you an idea of the worst conditions:

“A 2 apt house and garrett at Coldwell in Gourdon has 12 inmates – Males aged 43, 20, 18, 12, 10 & 5; Females aged 40, 19, 16, 14, 7 & 2. The house is seriously overcrowded. The kitchen has a capacity of 1243 cubic feet, and the room is of similar size. The garrett room is 354 cubic feet and 3 boys sleep here. The ceiling is ‘v’ shaped and at the highest part is 5ft 10in high. There are 2 enclosed beds in the one room and one in the garrett. The walls are very damp and embedded along the back. There are no eaves, gutters or conveniences. This was reported and the tenant strongly urged to look out for a larger house. The owner was also written to. On a later visit the enclosed beds had been removed and some other small repairs carried out. The tenant had failed to find a bigger house despite his efforts.”

The Kincardine County Sanitary Inspector felt that there had been a very quick shift from the “Homes fit for Heroes” attitude back to one of “Will it pay?” and “Where will the rent come from?” that was being fed by enduring middle class snobbery - the type that held onto fictional stories of the poor not understanding how to handle modern conveniences (e.g. storing coal in a new bath), squandering their money and other benefits, or their hardiness in the face of harsh conditions which allowed them to live into old age. All of this was a potential argument for doing nothing. His argument against this was a familiar one – the evidence suggested improved housing would produce social and health benefits that would save money further down the line, such as in health costs.

One option was for local authorities to build houses under the new housing legislation of 1919 (the Addison Act). Kincardine County district committees applied by the end of 1919 to the Scottish Board of Health for long term loans to build 130 new houses, and by Dec 1921 20 had been built – 10 in Gourdon, 6 in Drumlithie, and 4 in Ardoe.

Repairs to existing sub-standard housing was also possible under the Addison Act. Use of these powers was considered at Catterline, but there were concerns about whether this would be worth it in the long term with the declining population in the area: would an investment in repairs to housing be worth it if it went the way of Crawton, abandoned in 1910?

|

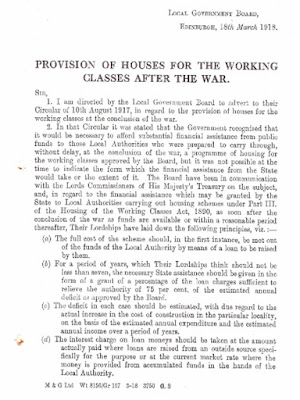

| Letter received by Deeside District Council relating to housing programmes |

Aberdeen

|

| Plans of Torry Housing Scheme, 1919 |

Moving forward to the present day, the Town Council's successor Aberdeen City Council recently completed 99 council homes at Smithfield and 80 at Manor Walk in Heathryfold as part of a new-build programme for 2,000 council homes: the biggest programme in half a century.

Fraserburgh

Fraserburgh’s situation also highlighted the lack of affordable accommodation, a problem exacerbated with the influx of thousands of workers for the fishing season. This became a significant driver for providing new housing in the country. Fraserburgh's Town Council developed an innovative housing scheme, approved by the Board of Health in 1919, for 186 semi-detached houses on a plot bounded by Dennyduff Road, Finlayson Street, Gallowhill Road and Union Grove. Described by the Board of Health as "one of the most successful designs that they have had submitted", the Press and Journal speculated that "when the scheme is complete, it might form a Mecca for town planning experts to visit".  |

| Plan of Fraserburgh Housing Scheme, published in the Aberdeen Press and Journal, 3 December 1919. Used by kind permission of DC Thomson & Co Ltd. |

Unfortunately, the Town Council struggled to obtain the necessary funding for the scheme. The costs spiralled to such an extent that the ratepayers ended up contributing more than the Government and eventually only the first installment of the scheme, 20 houses, went ahead on schedule (the site was further developed later in the 1920s). This is likely to have been houses to the north of the site, around Gallowhill Road.

There were complaints in the Fraserburgh Herald about the cost of the houses (£1200 per house) and the high rentals, which were too high for ordinary workers. It was also suggested that there was no need for additional housing, although the high number of applications (70) for the 20 houses would seem to suggest otherwise.

This complaint would seem to be born out by the list of preferred tenants agreed by the Town Council in November 1921. In line with the "Homes fit for Heroes", preference was explicitly given to ex-servicemen and the widows of men who were killed on active service: one of the larger 6 room properties was given to the widow of Lieutenant George Bradbury. A list of the 20 successful applications from the Town Council meeting in November 1921 supports the idea that these were not for the poorest workers: successful applicants were largely tradesmen, merchants and skippers, but a Dock Superintendent, teacher and MA were also listed.

Inverurie

Inverurie was an early adopter of the Housing legislation – it resolved in December 1918 to draw up plans for housing schemes at 2 sites in the town. From the period of its inception the Inverurie scheme had to reduce in a number of areas - the number of sites from 2 to 1 – sticking with North Street, and then moving to Falconer Place on 16 June 1919. Construction began on 10 houses at the Falconer Place site in April 1920.

By August 1921 the project had expanded to 3 housing schemes, but this eventually had to be abandoned as the Scottish Board of Health resolved in September 1921 not to take anymore contracts under the State assisted scheme from Local Authorities. Nevertheless, tenancies were provided for 27 properties throughout the period at an initial rent of £18 a year for a 3 roomed property, and £22 per year for 4 rooms until May 1927 (but warning that an inflationary increase may be required).

Inverurie’s selection criteria seemed to stick to the “Homes Fit For Heroes” line and resolved to give preference to former service-men (the same was true in Stonehaven with the housing constructed on Fetteresso Terrace). As with Fraserburgh, the tenants selected in Inverurie indicate a lower middle class bias – they included a nurse, teacher, butcher, even an organist - professional individuals with regular incomes to pay their rent.

By August 1921 the project had expanded to 3 housing schemes, but this eventually had to be abandoned as the Scottish Board of Health resolved in September 1921 not to take anymore contracts under the State assisted scheme from Local Authorities. Nevertheless, tenancies were provided for 27 properties throughout the period at an initial rent of £18 a year for a 3 roomed property, and £22 per year for 4 rooms until May 1927 (but warning that an inflationary increase may be required).

Inverurie’s selection criteria seemed to stick to the “Homes Fit For Heroes” line and resolved to give preference to former service-men (the same was true in Stonehaven with the housing constructed on Fetteresso Terrace). As with Fraserburgh, the tenants selected in Inverurie indicate a lower middle class bias – they included a nurse, teacher, butcher, even an organist - professional individuals with regular incomes to pay their rent.

The Housing Act also had an impact in rural areas of Kincardine, Banff and Aberdeen counties. The Kincardine County Sanitary Inspector reported on the poor quality of rural housing for the working classes in 1919, which in turn was leading to health problems including high infant mortality. The following example from the 1919 St Cyrus District Sanitary Inspector report will give you an idea of the worst conditions:

“A 2 apt house and garrett at Coldwell in Gourdon has 12 inmates – Males aged 43, 20, 18, 12, 10 & 5; Females aged 40, 19, 16, 14, 7 & 2. The house is seriously overcrowded. The kitchen has a capacity of 1243 cubic feet, and the room is of similar size. The garrett room is 354 cubic feet and 3 boys sleep here. The ceiling is ‘v’ shaped and at the highest part is 5ft 10in high. There are 2 enclosed beds in the one room and one in the garrett. The walls are very damp and embedded along the back. There are no eaves, gutters or conveniences. This was reported and the tenant strongly urged to look out for a larger house. The owner was also written to. On a later visit the enclosed beds had been removed and some other small repairs carried out. The tenant had failed to find a bigger house despite his efforts.”

The Kincardine County Sanitary Inspector felt that there had been a very quick shift from the “Homes fit for Heroes” attitude back to one of “Will it pay?” and “Where will the rent come from?” that was being fed by enduring middle class snobbery - the type that held onto fictional stories of the poor not understanding how to handle modern conveniences (e.g. storing coal in a new bath), squandering their money and other benefits, or their hardiness in the face of harsh conditions which allowed them to live into old age. All of this was a potential argument for doing nothing. His argument against this was a familiar one – the evidence suggested improved housing would produce social and health benefits that would save money further down the line, such as in health costs.

One option was for local authorities to build houses under the new housing legislation of 1919 (the Addison Act). Kincardine County district committees applied by the end of 1919 to the Scottish Board of Health for long term loans to build 130 new houses, and by Dec 1921 20 had been built – 10 in Gourdon, 6 in Drumlithie, and 4 in Ardoe.

Repairs to existing sub-standard housing was also possible under the Addison Act. Use of these powers was considered at Catterline, but there were concerns about whether this would be worth it in the long term with the declining population in the area: would an investment in repairs to housing be worth it if it went the way of Crawton, abandoned in 1910?

Comments

Post a Comment