What on earth does that say?

The majority of our Aberdeen City & Aberdeenshire records are handwritten (manuscript) documents or books. Many “official” records produced by Councils would have been written by Clerks or similar post holders with a good standard of literacy and where a legible hand would be key requirement, as the documents they produced were recorded to provide a reference to consult at a future date. But the further back you go, different styles of handwriting were in vogue. There is an increased chance of unusual spellings (this wasn’t standardised until the 18th or 19th century[1]), challenging hands that we aren't familiar with, or documents being written in Scots or Latin. These can be challenging for modern eyes to decipher!

Additionally unofficial records – diaries, letters, etc. – have wildly varying handwriting styles in different degrees of legibility, and often feature quirky spellings. It should be said that this isn’t restricted to older records: I’ve often been pulled up for writing something completely illegible on a production slip (sorry to all the Archive Assistants I've worked with!) or struggled to decipher something a colleague has written on a box, and we’ve all heard the cliché about doctors having bad handwriting.

The art of reading old handwriting is called “palaeography” and is something most archivists cover during the training they undertake for their Masters qualification.

This blog post is not going to discuss medieval hands (partly

because the Archivist writing it can’t read Latin!). If this is something you

are interested in, I would recommend taking a look at the Aberdeen Burgh

Registers project, which has been transcribing the first eight volumes of the

UNESCO-recognised volumes, to get a sense of how challenging a task this can be

(https://sar.abdn.ac.uk/).

I would also recommend a read of the Project Lead, Dr Jackson Armstrong’s, blog post on this

subject for a deeper dive.

We will instead be focusing on some examples of Secretary Hand. As the Scottish Handwriting website explains, this was “an administrative/business 'shorthand' used throughout western Europe” during the early modern period (roughly 1500-1750). This can be very challenging to read to a modern eye: some of the letters are written very different to our modern spelling and many abbreviations are used.

The examples I’m going to look at are from the House of

Correction Incarceration Book (more information about this item, with images and

a full transcription are available on our

website).

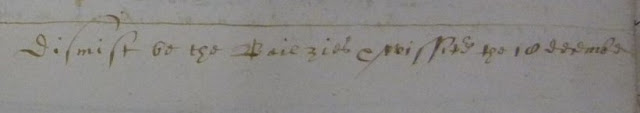

[Modern equivalent would be: Dismissed by the Bailies and

Visitors the 18 December]

In this line we can see that ‘s’ is the long s in “Dismist”.

‘h’ appears as a backward 3 in “the”. There is a yogh in the middle of “Baeȝlies”:

this is an Anglo-Saxon letter form that is no longer used, but would have produced a ‘yh’ sound (another

example of 'the' is the thorn, which appears like a ‘y’ and produces a ‘th’

sound, hence the common use of ‘Ye olde’). “Wissitrs”

contains an abbreviated ‘er’ at the end of the word, and demonstrates that v

and w (and u) could be used interchangeably. The ‘c’ in December appears

similar to our modern ‘r’. All the ‘e’s across the line appear backward, or

like a letter 8 (and confusingly similar to the letter ‘d’).

Taking the line across from this:

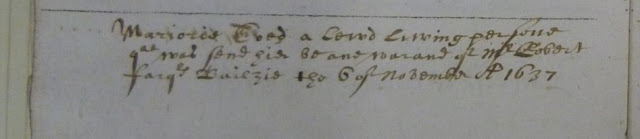

Mariorie Toed

a lewd liwing persone

qat was

send hier be ane warand of Mr Robert

farqrs Bailȝie the

6 of November A 1637

[Marjory Todd a lewd living person that was sent here by a

warrant of Mr Robert Farquhar, Bailie, the 6th November 1637]

This example shows another common set of abbreviations: “qat”

which is an abbreviation of quhat and equates to “what” in modern parlance;

and the bailie’s surname Farquhar is abbreviated to “Farqrs”. The A

before the 1637 indicates that the year is AD.

In both examples we see the use of “be” rather than “by”.

Another common issue we have with deciphering old documents is where letters with minims (short down strokes of the pen which appear in i, m, n, u) appear together, making them hard to distinguish. For example, from the Correction Book, the third word of the top line is Daniel but it could easily be read as Damel:

And in a more modern example:

This surname (of the the Dundee Harbour Commissioner’s Clerk from the Aberdeen Harbour Board collection) had us a little baffled (Saundus? Sanudus? Samidus?), but a check in the Post Office Directory for Dundee in the 1820s confirmed that the surname was "Saunders".

- The excellent Scottish Handwriting website produced by the National Records of Scotland: https://www.scottishhandwriting.com/index.asp

- UK National Archive’s online tutorial on reading old handwriting https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/

- Southampton University's Introduction to Palaeography https://www.southampton.ac.uk/archives/resources/palaeography.page

Comments

Post a Comment