By the Witch-Hunter’s Hand: Sources on the 1597 Witch-Panic

The witch-panics of the late Mediaeval period and their accompanying Commissions and Trials are some of the darkest times that the Burgh of Aberdeen went through – and it was a period that could easily have slipped from memory and history, but for the preservation of a few key records.

|

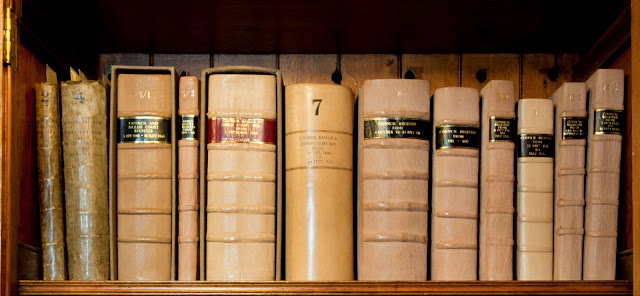

| Council Registers on shelf in Charter Room, Town House |

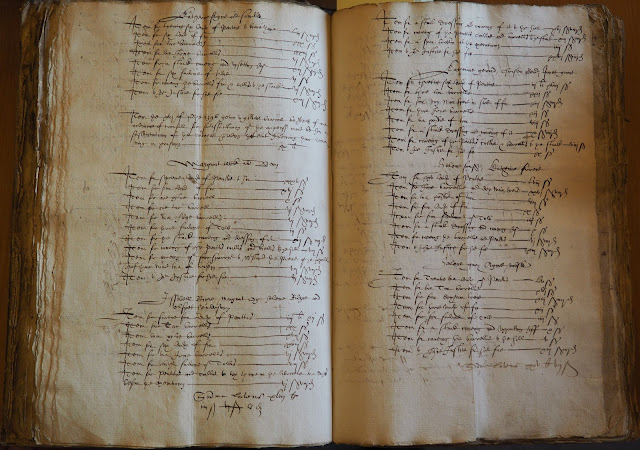

Dean of Guild's Accounts:

The early accounts are bound in a thick, uneven book with roughly-made covers of thick pulp and time-polished parchment. Each year was submitted as a loose paper pamphlet by a different elected Dean of Guild – each year looks different, feels different. It’s rare that the pages for two consecutive years are even the same size. Some are recorded on cheaper paper, with thinned ink that renders the writing scarcely visible.

.png) |

| Dean of Guild's Accounts |

|

| Dean of Guild's Accounts |

|

| Dean of Guild Accounts for costs relating to witch trials and executions |

Letter Books:

The process of trying cases of witchcraft was one that needed special permission of the Crown – permission that would have required presenting written evidence to the Privy Council, resulting in the creation and copying of several documents. Most of the town’s surviving correspondence was gathered and bound in a series of books of incoming letters – the first one covers the period from 1552 to 1633. Unfortunately, there is little material within this letter book referring specifically to the 1597 witch-panic. The 64th letter in the book is an act relating to the gathering of gold and silver bullion to furnish the Royal Mint, due to the scarcity of currency at the time. Pasted to the back of this is a completely unrelated document – a list of the members of an “assize” (a register of jurors for the trial of witches by a General Commission of Justiciary).

.png) |

| Assize from Letter Book 1552-1633 |

The next letter following is a demand on all ministers of the Church of Scotland, their elders and their deacons in Blelack, Tillylair, Kincardine, Wester Kincardine, Cushnie, and Woodside, instructing them to draw up dittays detailing the life and behaviour of specified persons, accuse them of witchcraft, and bring the documents to Aberdeen by the 6th of April, 1597.

Commissions of Justiciary:

In terms of records produced by the Burgh itself, we have reached the outer limit of anything that relates to the witch-panic of 1597. However, we haven’t touched on the core of the records that remain. Many of the sources in our possession are materials which wouldn’t have been expected to survive at all; materials that were retained through either chance or force of habit – materials that inform our whole picture of the witch-panic. They are the records of the town’s Commissions of Justiciary.

Witchcraft and Sorcery were taken very seriously, being criminal offences in Scotland since the passing of a statute in 1563. Though there was provision within that law to try accusations of witchcraft using the local courts, there was never any recorded attempt made locally to treat these crimes as anything less serious than the four “pleas of the Crown” – those being murder, robbery, rape, and arson, none of which could be tried by any court not appointed by royal authority. The most common way to apply for such authority was to request a Royal Commission, and the Burgh of Aberdeen did so twice between the winter of 1596 and the spring of 1597.

Aberdeen’s first commission was granted for the trial of certain named individuals – absolute in authority but limited in scope. Janet Wishart, her son Thomas Leys, her daughters, who are not named in the text of the commission, and Isobel Cockie are the only persons who were fit to be tried under the authority of the granted Judiciary. The Commission was issued on the 2nd of February 1597 and sentence had been carried out in its name within three weeks. The success of the first Judicial Commission carried the seed of a second within it. If any of those accused and tried by the court should, during their trial, name anyone not already on the list, then the commission was powerless to pursue action against them. With this in mind, the Burgh applied to the Crown and Privy Council for a second Commission. This one, however, was not limited by name – it was limited by time.

For a period of five years, the General Commission of Judiciary allowed Alexander Rutherford, Provost of Aberdeen, as Commissioner and Thomas Leslie as his Depute to try anyone suspected of witchcraft or sorcery, as well as anyone accused of trafficking with a suspect. Potentially, the Commissioners were of the belief that the roots of the menace would take them years to eradicate. Letters were sent throughout Aberdeenshire to the Protestant ministers in the towns and villages of the hinterland, instructing them to gather testimony on named individuals – to prepare dittays, to lay the groundwork for witch-trials. Co-operation in this benefited both the Commission and the Church – the courts would have been supplied with a steady stream of supporting documents, and the resulting trials would ensure that the parishioners were exposed to a salutary and graphic example of what happened to those who strayed from the path outlined in the Minister’s sermons.

The Judiciary appointed by the Royal Commissions had no real requirements in terms of legal qualifications or learning – this much is almost immediately apparent when examining those records still extant from the period. The courts that were set by Judicial Commission were legally binding and remarkably ad hoc. The survival of any records from the trials is itself surprising – the sentences of the Court were enacted almost immediately, obviating the need for an appeals process, and the administrative officials of the Court were local magistrates and burgesses. They had no training or experience in trying serious crimes, and the Commission was by its nature incapable of surviving the enactment of its final verdict. There was no machinery in place to retain the details of these trials in the long term, and yet a surprising amount managed to survive to the present day.

Even though the Commission was formally dissolved at the conclusion of its stated and appointed business, some of its papers were retained – though by whom exactly, it is impossible to say. Many survived until the 19th Century, long enough to be transcribed and published by Victorian antiquarians. Some survive to the present day and are available to be consulted by the public at the Town House in Aberdeen. The reason behind their survival can only be guessed, but is likely to be spurred by one of two motives: either as a receipt for the Dean of Guild’s efforts in administration of the witch-hunt, or as evidence to the Privy Council of the Commission’s necessity

Dittays:

Much of what survives in terms of the Commission’s records relate to the early part of the procedure of a witch-trial. The bulk of the records are compiled dittays – lists of accusations ranged against the victims of the hunt – as well as much rarer confessions, usually produced later in the Commission’s life to shore up a draft dittay or to submit to the Privy Council.

|

| Dittay against Isobel Strathanchyn, accused of casting charms and necromancy. |

Some of the surviving dittays are obviously draft copies or pre-trial versions of the final accounts that would be put to the assize. These show us a number of things: to take the example of Jonet Wishart’s dittay, the manner of recording makes it clear that she had no legal representative to argue in her defence. The accusations, listed point by point, have notes in the margins of the page such as “denyit evir he sent for hir befoir his decease”, usually countered with a curt statement such as “proven by Thomsoun.” In the eyes of the appointed Commission, and all too frequently in the opinion of the assize, the testimony gathered in the dittays was sufficient proof for conviction. Any argument put forward by the accused in her defence is phrased as “denyit”, and usually swatted aside by a flat “provin.”

First Miscellany of the Spalding Club:

[Martin Hall, Archivist]

Make an appointment at our Town House site to visit and view these records: archives@aberdeencity.gov.uk

Comments

Post a Comment